A few keepsakes from late Victorian Stockton-on-Tees. They belonged to Miss Eleanor Bateson of 37 Skinner Street.

Eleanor was born on 21 November 1866 to John and Mary Bateson, the fourth child of a family of six.

Her father was a cordwainer when she was born – not a cobbler who repaired shoes, but a man who made shoes from new leather – but when she was a little girl he became firstly a foreman in a local ironworks and then a school warden for Stockton, responsible for enforcing school attendance by calling on parents and visiting schools. It was quite an onerous position.

These keepsakes and chance survivals of a long life date from Eleanor's twenties and early thirties.

To begin with the Christmas season –

Eleanor kept two particularly attractive Christmas cards. One of them shows a spray of ivy and the message "A Happy Christmas". Folded, it measures 3 inches by 2 inches, and it opens out to reveal a quotation from Shakespeare's Sonnet 30 and a verse by Thackeray.

We might not think the verses very Christmassy but they send wishes for "Good Health and Good Fortune" to an absent friend.

The second card is rather larger, measuring when folded 5 inches by 3 inches. "With Louie's love to Nellie" is written on the reverse. The picture shows strawberries and strawberry leaves together with a little scene of a house by the sea. "Good Wishes" is the message on the front.

Inside is a verse by

Helen Marion Burnside (1841-1923), an artist and writer of lyrics and verses. The verse inside this card begins

Happy Christmas to you.

Best of earthly blessings

Fall on you to-day

A collection of small, brightly-coloured paper scraps shows that Eleanor kept a

scrapbook.

These are all that remain of the sheets of embossed relief images and die-cuts that she bought to fill her pages – but we don't have her scrapbook, so we can't see how she arranged them and what sort of artistic effects she achieved.

The next memento shows that Eleanor was a singer.

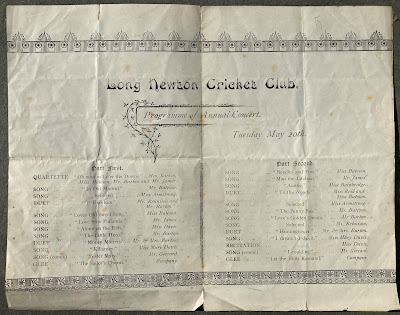

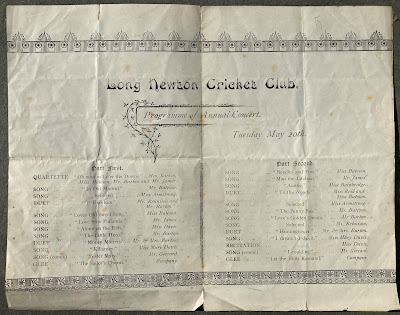

The Programme for the Long Newton Cricket Club Annual Concert is simply dated Tuesday May 20th. The year isn't given, but 20 May fell on a Tuesday in 1890 and in 1902. I rather think the concert might have taken place in 1890. Quite a few of the pieces date from the 1880s and listening to fairly new songs would have been part of the attraction.

We don't know if Eleanor was in an ensemble that sang for the Long Newton Cricket Club's fundraiser or if she was involved in the Club itself. And was the Mr Bateson on the programme her father or her brother? We don't know. Perhaps it was both of them, one of them giving a rendition of the music hall comic monologue

'The Penny Bus' and the other singing the romantic ballad

'In Old Madrid' (which you can listen to in a 1920 recording

here).

Eleanor appears four times in the programme. She opened the concert in a quartet singing

'O Who will o'er the Downs so free?' and followed it up with

'Love's Old Sweet Song', which we might remember better as 'Just a Song at Twilight'. She opened the second half with 'Needles and Pins', which I suspect must have been a comic song, and then she sang in a duet. And both halves of the programme ended with a glee sung by all the company.

Besides music, Eleanor also loved poetry. In the late 1880s she bought a dark red, hardback exercise book measuring 7 inches by 9 inches – it was her Poetry Book.

The first poem she transcribed into her book was "Newly Wedded" by Lizzie Berry. This probably came from a recently published book called Heart Echoes: Original Miscellaneous & Devotional Poems, which came out in 1886 and is available in a reprint today. Lizzie Berry came, her publishers explained in their foreword, of a humble background and had suffered "great trials and difficulties". Her verses were often printed in the newspapers and she came to have a devoted following.

But Eleanor also liked older verse and classics such as Shelley, Cowper, Thomas Moore and Longfellow. And she read novels – she had been reading

A Romance of Two Worlds by

Marie Corelli. Newly published in 1886, it was Marie Corelli's first book and an immediate popular success – and the beginning of a highly colourful career. Eleanor was clearly taken by it and she transcribed verses from the novel into her poetry book.

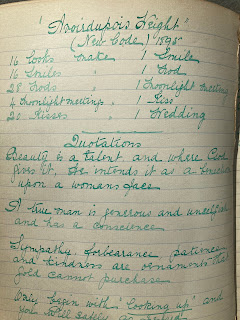

She didn't confine herself to poetry. When she saw something that amused her, she copied it out. Some of us will remember Avoirdupois Weight – which usually went like this

16 oz (ounces) = 1 lb (pound)

14 lb = 1 stone

28 lb = 1 qtr (quarter)

4 qtrs = 1 cwt (hundredweight)

In 1895, when Eleanor was 29 years old, she was taken with a gently humorous, sentimental version:

Avoirdupois Weight

(New Code) 1895

16 Looks make 1 Smile

16 Smiles make 1 Nod

28 Nods make 1 Moonlight meeting

4 Moonlight meetings make 1 Kiss

20 Kisses make 1 Wedding

One of the quotations on the same page reads, "A true man is generous and unselfish and has a conscience."

The notebook is far from full – Eleanor only filled a dozen or so pages. The last poem of all was part of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's 'A Psalm of Life' (1838), which begins

Tell me not, in mournful numbers

Life is but an empty dream!

Eleanor transcribed verses 6 and 9:

Trust no Future, howe’er pleasant!

Let the dead Past bury its dead!

Act,— act in the living Present!

Heart within, and God o’erhead!

Let us, then, be up and doing,

With a heart for any fate;

Still achieving, still pursuing,

Learn to labor and to wait.

In 1901 Eleanor was living at 37 Skinner Street with her parents, her brother Malcolm and a young lodger, who was a grocer. She was working as a clerk in a tea warehouse.

I expect the tea warehouse stood at 29 The Square (where the library stands today) and belonged to William Thomas Trattles. In the late summer of 1906, as she approached her 40th birthday, Eleanor married him.

A year after the marriage, Eleanor gave birth to her only child, Mary, born on 31 October 1907. It was Mary who kept her mother's poetry book and the other little keepsakes, a small collection surviving by chance from a family's accumulated mementos.

Mary was only 14 when her father died, so she must only have had a child's remembrance of him. He must have been a man of determination, energy and business acumen; he was certainly someone who knew personal tragedy.

William Thomas Trattles was 11 years older than Eleanor, a widower with 5 children – the youngest was 11 and the oldest was 21.

He was born in 1855 in Staithes, the son of a master mariner. For many years – for all of Mary's lifetime – a picture of the sailing ship

Zephyr had pride of place above the fireplace. The

Zephyr was built in 1845, master John Trattles, owner Thomas Trattles, her destined voyage was Hamburg and she was rigged as a

snow. (And you can examine her survey on the Lloyd's Register Foundation Archive

here). When John Trattles retired from the sea, he was for some time a grocer in Staithes. Perhaps this was perhaps the impetus for his sons Matthew and William to go into the tea trade.

In 1880 they were in business together as Trattles Brothers, tea and coffee merchants of 29 The Square. But the partnership only lasted 3 years and they split up in 1883. They must have agreed that William could keep on the warehouse at 29 The Square because he carried on there as a tea wholesaler.

William built up the business, advertising heavily to tea dealers in the Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough – one of his selling points was that he was the "Sole packer of the celebrated Sultan Packet Tea". He prospered, diversifying into Fancy Goods, Glass and China. His December advertisement for 1891 proclaimed

Christmas and New Year Presents – the largest and best assortment in the district at W T Trattles, 29 The Square, Stockton. Dinner Sets, Chamber Sets, Toilet Sets, Tea Sets of endless variety to choose from, and all at wholesale prices

He tried branch shops for a while – the shop in Middlesbrough was on the "main thoroughfare" but it didn't work out and he put it up for sale in 1892 ("would suit a lady"). The shop in Darlington lasted longer. He advertised it for sale in 1903

To be disposed of, an old-established Present, Tea and Fancy Goods Business, in Darlington; satisfactory reasons for disposal; managed by a female.

Meanwhile, he and his wife Agnes Jemima Wilson and their growing family progressed from 24 Balaclava Street, in the network of terraced streets near the railway station, to 13 Palmerston Street – where they had a live-in servant – to Park House on Richmond Road, next to Ropner Park. It was a villa with "12 large, spacious rooms, with all conveniences, large garden and grass lawn; adjoining Park; very best position".

And it was there, on 29 May 1895, only three weeks after giving birth to her sixth child, that Agnes died at the age of 40. William was left a widower with five children – their first baby, Agnes, had died within weeks of her birth. Ida was the eldest at 13, and after Ida came Hugh Harold, William Horace (always called Horace), Agnes and the new baby Thomas.

William picked up his life and carried on. He had his business, he was a town councillor, and he employed a housekeeper. The children were growing up and Hugh Harold started work as a Chartered Accountant's clerk. Then disaster struck.

On 8 April 1902 a fire at the shop and warehouse in the The Square gutted the building and destroyed a great deal of the stock. A few months later, on 26 July, his beloved daughter Ida died at Park House. I'm not sure if his heart was in the business after this, or perhaps he no longer had the drive to rebuild the business. At any rate, by the time of the next census in 1911 he was no longer an employer, but was working as a Commercial Traveller for China goods.

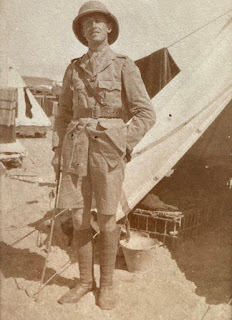

When the First World War broke out, little Mary was nearly 7 years old. Her eldest brother Hugh Harold was 29, living in Beckenham and working as a bank clerk. He joined the 24th Battalion Royal Fusiliers as a private. Horace had been living at home in 1911 and working as a drapers' assistant. When war broke out he joined the 14th Battalion London Regiment as a Private. Thomas was a merchant seaman. He joined the Yorkshire Regiment in December 1915 when he was 20. Their sister Agnes was 23 years old. I think it was probably during the War that she trained as a nurse, the career she followed for the rest of her life.

|

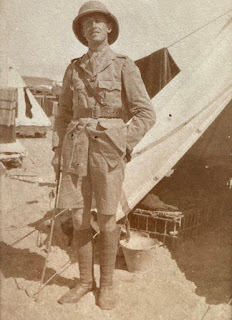

William Horace Trattles

(1890-1917) |

Mary adored her brother Horace, he was her favourite brother. In June 1915 he was commissioned 2nd Lieutenant in the 13th Battalion Hampshire Regiment. In the spring of 1916 he was attached to the 9th Battalion Worcestershire Regiment and sent out to Mesopotomia. He was killed in action on 25 January 1917 at the age of 26. He is buried in the

Amara War Cemetery in south-east Iraq.

Mary had prayed for him fervently every night; she never believed in God again.

By the time of Horace's death, Hugh had been wounded twice and was back in the trenches, and Thomas had been in hospital for 6 months.

He had been sent out to France towards the end of April 1916 but was wounded within weeks. The damage – I think he was left with epilepsy – that was caused by the gunshot wounds to his head on 12 July 1916 incapacitated him from work for life.

Hugh Harold Trattles died in 1920 at the Phillips Memorial Hospital in Bromley, Kent, aged 35. His father William Thomas died the following year at the age of 66.

So only Mary, her mother and her brother Thomas were left in Stockton. They lived at Rosebank, a house with 5 bedrooms and 3 reception rooms on Cranbourne Terrace, where the family had moved in 1915.

Rosebank stood on a large plot and its garden stretched back to the railway line – which meant it was naturally called into use when the centenary of the Stockton to Darlington Railway was celebrated on of 2 July 1925.

A grandstand was built at the bottom of the garden for dignitaries and notables to watch the grand

Railway Centenary Procession of locomotives going by.

Locomotives of all types and ages, passengers and crew in period dress, the Darlington Band playing from one of the rear wagons, a tableaux train carrying a pageant illustrating the evolution of the wheel in transport, luxury trains – the Flying Scotsman carrying excited children – and in pride of place a replica of Locomotion No 1, led by a horseman flourishing a red flag to warn of its approach. It was an enormous success and you can see newsreel footage of it on youtube today

here,

here and

here.

|

| Mary Trattles |

Eleanor, Mary and Thomas lived at Rosebank for about 20 years. Mary, it is said, was engaged to be married but she had her mother and brother to care for, and the engagement was ended.

By the time the Second World War broke out they had moved to Stirling House, 98 Darlington Road, Hartburn. Eleanor died there in 1952.

Mary lived on there until her death in 1998, long outliving her brother Thomas and sister Agnes. She was the last of the family.

Her most vivid memory to the end was her beloved brother Horace carrying her piggy-back as he raced round the garden, her mother calling anxiously all the while, "Be careful! Be careful! You'll drop her!"

.jpg)